Who was Robert Mueller? Reflections on History, Segregation, and Place Names

A few weeks ago someone sent a query to my neighborhood’s listserv asking whether the Mueller neighborhood should be pronounced “Mew-ler” or “Miller.” Several people wrote back, explaining that the neighborhood got its name because it occupies the site of Austin’s old municipal airport that itself had been named for a former City Council member, Robert Mueller, and that descendants of his say that the name is pronounced “Miller.” (See also this story by KUT). One person wrote that she has always pronounced it “Miller” in “homage to Robert Mueller.”

This got me wondering about who this man was that moved the Austin City Council to name its airport in his honor and to whom we continue to pay “homage” by having one of the highest-profile neighborhoods in the city named for him. (The Mueller development is well known nationally and internationally in urban planning and development circles for its pioneering of New Urbanism infill development).

In order to find out, I tried looking up explanations for why the city named its first municipal airport after Mueller. According to a web page maintained by the Austin History Center, the airport was named for Mueller, who died in January 1927, “just months after being elected to office,” in order “to honor his dedication to service and his civic contributions” (http://www.austinlibrary.com/ahc/faq12.htm). He had been elected to the “city commission” (as they called the Council then) and began serving in July 1926, often as acting mayor; the following January, after having fallen ill during a late-night Council debate on the city budget, he died of an infection brought on by hay fever. This got me wondering what Mueller could have contributed to the city in just a few months in office that merited such an honor.

What I found out is that the career of Robert Mueller offers a glimpse into how racial segregation became institutionalized in our local government and built into the landscape of Austin. This history also raises the question of how we recognize and confront that past today.

I began my inquiry into Robert Mueller by reading through the archives of The Austin Statesman and The Austin American, the two newspapers of the day in the 1920s. I learned that Mueller was scion of one of Austin’s early settlers, that he was one of four brothers prominent in the business community, that he owned a luggage factory with one of the brothers and a jewelry store on Congress Avenue with his father-in-law, that he was active in the Chamber of Commerce (which was headed by his brother Carl), that he was a Rotarian, and that he was the scoutmaster and founder of the local Boy Scouts organization. His wife, Leona née Mayer, was active in local charities and civic organizations, and the family was often featured in the society pages of the newspapers, such as in a 300-word article on his son Harold’s sixth birthday party that appeared in The Austin American on January 31, 1926.

In other words, when Robert Mueller ran for Austin City Commission in 1926, he was already a member of Austin’s ruling elite.

In fact, it seems that Mueller ran in 1926 precisely because he was one of Austin’s leaders. 1926 marked the culmination of more than a decade of local government reform that began with the elimination of the “ward” system of geographical representation and the adoption of an at-large system in 1909. The 1926 election saw the implementation of a new “commission-manager” form of government, in which a city manager, much like a corporate CEO, would be responsible for running the government under the broad direction of the Council, which acted much like a corporate board of directors. Both of these reforms were intended to break up the old patronage system and install a modern, bureaucratic, and professional form of city government that would better serve local business interests (Tretter, p. 123-127).

According to numerous newspaper articles, Mueller “led” the “manager ticket”: a slate of five business leaders who all won election in a landslide, with Mueller pulling in the most votes (at the time, there were no “positions”; the top five vote-getters became the City Council).

Analyzing this new form of government in 1939, social scientists Harold Stone, Don Price, and Kathryn Stone summed up the job facing Mueller and his colleagues:

“This council was faced with the task of putting a new form of government into operation and inaugurating a tremendous volume of new services. The government had to be reorganized …There were advisory boards to be appointed for parks, library, and other services. The contract for sale of the electric light plant had to be considered; public health matters were very bad; and departments were disorganized. The new council hardly knew where to start, there were so many sore spots needing urgent attention. …They thought of themselves as directors of a corporation, not as members of a legislative body with obligations to their constituents.” (Stone, Price & Stone, p. 31-32)

At its very first meeting on July 1, 1926, and just minutes after being sworn in, the new Council passed Ordinance 260701-1, which established Austin’s modern administration by creating the departments of Law, Finance, Police, Fire, Public Health and Welfare, Public Property, and Water Light & Power. This was the formal beginning of the reorganization of local government under the new manager-commission system.

Austin was not alone in this. Cities across the country were embracing “Progressive” ideas that local governments should provide robust public services such as trash collection, recreation facilities, fire protection, etc.; enact regulations to protect public health and safety; and reorganize and enhance the physical infrastructure of their cities to advance economic interests. For example, in addition to creating the new departmental structure for the city, in their first few months Mueller and his colleagues created comprehensive traffic regulations and began regulating milk standards in the city, as I learned from reading the archives of the City Council minutes. The term “Progressive” might be misleading today because it connotes a certain politics; a more accurate description might be “pro-active” in the sense that the “Progressive” era was marked by local governments taking a more active or interventionist role in economic and social development through regulation, infrastructure building, and the provision of services. Prior to this period, local governments provided few services.

Perhaps the most well-known artefact of that era is the infamous 1928 master plan that not only implemented the new planning tool of zoning in order to increase economic efficiencies and boost land values, but also spelled out a mechanism for spatially segregating the city along racial lines: new local government services, such as parks, trash collection, and sewer hookups, would be provided separately for whites on the west side of town and people of color on the east side, thus forcing people of color to move to areas where they could receive these services.

These two interests—racial segregation and economics—cannot be separated. In order to create a “good business environment” in the downtown area and secure investment in land and real estate, civic leaders believed, people of color needed to be moved out of the west side of town, which would become a purely white space. The value of this “whitened” landscape would be increased by moving all of the people of color (as well as industry), who were seen as bringing down land values, to the east side, where the land would be much less valuable in comparison. In other words, in order to increase and stabilize land values and investment prospects on the west side, all of the “land uses” that were seen as less valuable, including residence by people of color, had to be grouped together and moved to a designated area of lower value. As geographer Laura Pulido explains, “the value of black land [in cities] cannot be understood outside of the relative value of white land, which is a historical product. White land [becomes] more valuable by virtue of its whiteness” (p. 16).

The creation of this uneven landscape of value—what geographers refer to as “uneven development”—was central to the ambitions of the business community and their taking control of the City Council and reorganizing the local government.

While the master plan was not adopted until after Robert Mueller died, it was set in motion during Mueller’s tenure on the Council: at one of the last meetings before he fell ill (Dec. 16, 1926), Mueller voted to create the City Plan Commission, which was responsible for heading up the initiative, including identifying and working with the Dallas-based consultants, Koch & Fowler, who wrote the plan.

Typically, when the 1928 segregation plan is brought up, it tends to be discussed as if its creators were anonymous or that the plan itself caused Austin to be segregated; in truth, of course, it was people—specific individuals—who helped create the segregated and unequal city that we are trying to reckon with today, and Robert Mueller was one of those people. He was one of the architects of the massively unequal city that we have inherited.

In addition, the 1928 Koch & Fowler plan did not begin the process of creating this new divided landscape in Austin; it merely systematized into a comprehensive framework the program and priorities of the new commission-manager government. In fact, the Council had, from the beginning of its work in July 1926, conceived of the new city administration and services as segregated. For example, on October 28, 1926, the Council voted to endorse a parks plan prepared by the Playgrounds and Recreation Association of America in conjunction with the Lions Club of Austin. The plan would create a new parks and recreation system (as opposed to merely maintaining a few parks), complete with permanent staff positions. According to the Austin American (Oct. 10, 1926), the plan called for separate facilities for Latinos and African Americans on the east side, two years before the Koch & Fowler plan recommended the same. In fact, two months earlier, Mueller himself was quoted in the Austin American (August 11, 1926) on the issue: “At present the Negro population of our city has no such facilities [a park or pool] and the council is sold on the proposition of providing the separate park and swimming pool for them…The negro residents of our city have never complained about the lack of this improvement in their section and the council feels that this need should be remedied.” Of course, African Americans had “no such facilities” only because they were barred from using existing public parks and pools.

In his book Racial Dynamics in Early Twentieth-Century Austin, Texas, historian Jason McDonald writes, “The Business Progressives were very paternalistic and patronizing in their dealings with African Americans, who were expected to show gratitude for the provision of the separate and inferior facilities that would not have been necessary at all if racial segregation had not existed. Referring to the fact that African Americans were excluded from the city’s existing parks, Adam Johnson [Austin’s first city manager] stated [in 1928]: ‘You helped pay for Barton Springs and we believe you are entitled to a municipal recreation center of your own’” (p. 235).

At the same meeting where they adopted the parks plan, the Council also voted to designate the first plots in “a burial ground for colored people” at Evergreen Cemetery, the city’s first municipal cemetery for African Americans, on East 12th St., in what was then far east Austin (actually, outside the city limits). The Council established prices for these plots, ranging from $15 to $35. During the same meeting, the Council also designated plots in one of the City’s other (white) cemeteries, the Oakwood Cemetery Annex, which lies just east of Comal St. between today’s East MLK St. and East 14th St. Plots here were priced from $55 to $150. This clearly reflects the way the Council used the separation of land associated with whites and blacks to create a geography of unequal value, one that made “white” land more desirable and therefore more valuable, only by creating devalued “black” land elsewhere.

And this geography is still with us today. Plots are no longer available in the Oakwood Annex, but there is still room at Evergreen, where plots sell for $1850, according to the City of Austin Cemetery Operations 2019-2020 Fee Schedule. In contrast, the only other City-run cemetery with available plots is Austin Memorial Park, on the west side near MoPac, where plots cost $2775 (1.5 times those in Evergreen). The inequality of land values today between these two City-run cemeteries, one on the east side and one on the west, is a direct result of the work of Robert Mueller and his colleagues in the 1920s who reorganized Austin, both spatially and administratively. That was the project of the “commission-manager” type government that Mueller helped create.

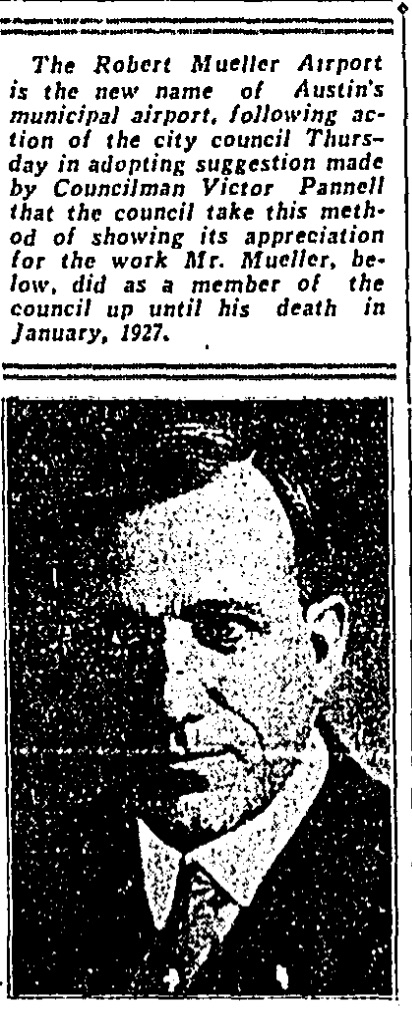

When, on April 10, 1930, the Council voted to name Austin’s first municipal airport (itself part of the project of enhancing Austin’s infrastructure to satisfy the the interests of local businesses) after Mueller, it was this work on the Council that they cited, according to an article in the Austin Statesman of that same day:

“The Robert Mueller Airport is the new name of Austin’s municipal airport, following action of the city council Thursday in adopting suggestion made by Councilman Victor Pannell that the council take this method of showing its appreciation for the work Mr. Mueller…did as a member of the council up until his death in January, 1927.” (Mueller’s brother, Leo, was on the Council in 1930 but abstained from voting on this resolution.)

Robert Mueller was a key member of the white business-elite leadership responsible for formally segregating Austin starting in the late 1920s with the reorganization of the city government that he spearheaded. He was one of the architects of the system that institutionalized white supremacy for generations of Austinites through the physical reorganization of urban space, which included the creation of a landscape of uneven value across the city and the building of new infrastructure, as well as the administrative reorganization of Austin’s government.

Recently, and especially this past summer, we have seen many calls to address the legacy of segregation in Austin, from the removal of Confederate statues at UT and the renaming of Austin schools and streets associated with the Confederacy to the re-evaluation of uneven policing practices. A major emphasis of the continuing battle over the rewrite of the city’s land development code (the zoning regulations) has been to address the historic and continuing segregation of the city and the unequal burden of growth on the historically devalued east side. Recent AISD elections have been fought around addressing the historical and continuing unequal distribution of education resources across the city.

This makes me wonder whether we should be continuing to honor Robert Mueller by having a high-profile neighborhood (and a street) named for him. My intention is not to argue for the removal of Mueller’s name from the landscape but to add to current discussions about how to meaningfully address the legacy of Robert Mueller’s generation by telling the full story of the Mueller name in the context of Austin’s historical development.

The airport was named after Robert Mueller to honor his work in modernizing Austin, a project that, from the beginning, was centrally concerned with racial segregation and fundamentally grounded in white supremacy. These facts are much more important than how we pronounce his name.

Rich Heyman teaches American Studies and urban planning at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

McDonald, Jason. 2012. Racial Dynamics in Early Twentieth-Century Austin, Texas. Lexington Books.

Pulido, Laura. 2000. “Rethinking Environmental Racism: White Privilege and Urban Development in Southern California.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90(1): 12-40.

Stone, Harold A., Don Krasher Price, and Kathryn H. Stone. 1939. City Manager Government in Austin, Texas.Public Administration Service.

Tretter, Eliot. 2016. Shadows of a Sunbelt City. University of Georgia Press.

Mr. Heyman,

Interesting, good ,thoughtful essay. But wasn’t it state law that forbid mixing of white and black citizens in swimming pools, restaurants, schools etc? Can we give our forefathers the benefit of the doubt and forgive them for trying to accommodate state law, feelings, and customs? After all I believe they were mostly conscientious Democrats at that time who passed those laws after reconstruction? I have seen that one is more likely to have something named after her/him if he/she dies while serving in office.

In 1957, three other white friends and I “could not be served” in the best looking cafe in the area on the Gulf Coast because it was a black owned business. When we asked why we were not being waited on, the waiter said “you know how it is”. Unfortunately our Black brothers would have had to drive much further than we to eat if they were not served in that cafe.

Isn’t there more important issues than names that you and your department colleagues could be spending energy on? What can be done to reduce the number of “fatherless” families. Many think that the presence of a father and mother in the home are really strong factors in a child’s success in school and life.

Is changing the name of our city on your radar? S.F. Austin not only owned slaves but traded in them. How about Republic of Texas president M.B. Lamar’s genocide of the native Americans in East Texas?

I really appreciate you giving the proper pronunciation to Muellar. I do not live in the development but I have to go there to get groceries, gas, and a ATM. I personally think they are building a lot of tacky buildings there.

Robert Mueller’s biography is eerily similar to that of Elisha Pease of Pease Park fame.

AMAZING- great read

Hi Rich. My name is Koreena Malone and I live in the Mueller neighborhood. And no I don’t pronounce Mueller “Miller”, lol! I’ve lived in Austin for 39 years and I always (as did everyone else I know) pronounce using Mue and Mi.

I can’t thank you enough for this information. I describe myself as an Accountant by day and agitator by night (aka Community Organizer). I actually organize a lot around affordable housing, but I find I spend most of my time as an MNA Steering Committee member and Chair of the Engagement and Inclusion Committee. In these roles I work with neighborhood leaders around racial equity issues.

So often we know that families / individuals especially white, CIS, upper class wrote their own narratives. In doing so, we learned what they wanted us to know. Taking a deeper dive and addressing facts is necessary for anti-racism work. It was just such a breath of fresh air to read your article.

And I can’t tell you the amount of people I have had a one-on-one’s with that would state “Mueller was a brown lot” or “Mueller didn’t gentrify East Austin”. It was a common to hear if your white this is a great neighborhood, but if your a POC, it is hard living here.

We have a Mueller Housing Engagement Team we we are working with Catellus, Housing Works, Mueller Foundation and Community Wheelhouse to address the policies that continue to exacerbate the inequities in this neighborhood. It’s hard work, but changing the policies to really center BIPOCs has been very difficult.

We may have a ‘progressive’ city, but boy we continue to pass racist laws that make it hard for BIPOCs to live and thrive.

And I couldn’t agree with you more…”These facts are much more important than how we pronounce his name.”

I have only been here in Austin for three years. I am very interested in this overgrown city but I have not been able to recognize the racist laws passed by council since I have been here. Please educate me. Thanks

I moved to Austin in 1973 from Washington, D.C. wher I was born and raised. I ALWAYS heard the airport pronounced as Mueller, not Miller and this pronunciation I learned from Austin old timers. Just wanted to add my 2 cents worth.