A Wrench in the Wheel

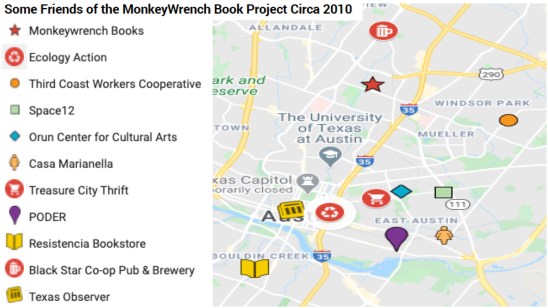

Prescript: This entry is based on a paper written in 2011 by Drs. Lauren Martin and Eliot Tretter, both geographers interested in alternative productions of space. We authored the essay before Occupy Wall Street popularized many of the modes of governance presented in the paper. We originally submitted it to a journal of radical geography as a non-research intervention, but the journal asked for revisions before potential publication. However, shortly after that report, Lauren moved to Finland and Eliot to Canada, and new responsibilities prevented them from returning to the essay. Recently, Eliot realized how much it reflects a moment in time inAustin during the 2000s, particularly because many of the businesses and groups mentioned in this report either exist in quite different forms or no longer exist. It should be mentioned that the broad range of groups and organizations that existed in Austin at this time governed by consensus principles. Included in this entry is a primitive map Eliot created in 2011 using GoogleMaps, and a quick Google search reveals how few of these organizations remain.

Even MonkeyWrench, the topic of the paper, has change substantially. MonkeyWrench remains a bookstore and community space just north of Hyde Park. The store was kept open by selling books, hosting events, and fundraising. It provided a community space that has been important for political mobilizations and it continues to host events that engage with community concerns. The store is still managed by a collective group, andLauren and Eliot were both members, overlapping from 2009-2010. Like other anarcho-projects, it fashions itself as a utopian space, a place governed by a sense of radical organization and collective (re)vision. In this entry, Lauren and Eliot explore both the possibilities and the limits engendered by MonkeyWrench’s consensus process, space of openness, and relationship to the state. They reflect on the difficulties of building collective memory, consensus, and inclusion and how the radical openness of MonkeyWrench, the lack of an overarching vision to contain its possibilities, in many ways helped the organization to succeed. Moreover, some readers many find this essay interesting because while MonkeyWrench Books certainly has unique aspects, the essay discusses an organizational structure that may be familiar. Its collective governance is characteristic of many radical community spaces across the world.

Lauren & Eliot, January, 2020

——

A Wrench in the Wheel:

Reflections on Radical Consensus and Democratic Space

From 2009-2010, we both volunteered at MonkeyWrench Books in Austin, Texas, and this essay critically reflects on our experience with this collective project. We use the term “MonkeyWrench Project” (MWP) to refer to the bookstore and the radical community that it supported. As we go on to discuss, the bookstore has always been more than a bookseller. The store is financed by a mixture of selling books and collecting donations and staffed entirely by volunteers; an organizing collective runs the MWP on an anarchist model of radical consensus, which became more well-known during the Occupy Movement. While book-selling finances the project and is its publicly commercial goal, MWP’s overarching political purpose is to create an enduring space for radical thought and action in Austin. While an average afternoon might find a few people browsing the shelves, the store also hosts film screenings, music events, book readings, artistic events, and public talks a few times a week. Part of a larger national and international network of infoshops and workers’ collectives, MonkeyWrench has become not only a fixture of Austin’s radical community, but a place for touring authors, film directors, and musicians to present and perform. MWP provides important infrastructure for a wider network of anarchist and radical movements as well.

Our time at Monkeywrench led us to believe that, for all the discussion in our disciplinary field of Geography about political spaces and spatializations, there needs to be more reflection on existing spaces of radical democracy. There is a tendency to treat these aspirations as merely abstract ideals, but MonkeyWrench is a place that attempts to adhere to the principles of difference and diversity. It is a place where many of the ideas of radical pluralism, actually existing-socialism or capitalism, and diverse economies are actively negotiated, performed, and emplaced. As we wrote this piece, corporate-owned mass media puzzled itself over the ideological demands of Occupy Together. If these various occupations had a common thread, it was an attempt to hold onto a political process: horizontal, consensus-based organizing. While calls to sharpen the occupations’ policy platform came from left, center, and right, our experience with MonkeyWrench makes us think that occupiers’ refusal to forsake process for platform might have been a source of the movement’s strength, though also one of its dangers. As debates over process and political platforms unfold, our reflections on the MWP highlight some of the promises and tensions facing actually existing radical democratic spaces.

Monkeywrenchin’: Making Space for Books/Action/Possibility

In 2001 a group of people who had been loosely organized around an alternative newspaper (the Javelina) and other local activists decided that there was great need for a community-run radical bookstore and community space in Austin. It seemed that selling radical literature and providing a place for the discussion of radical ideas could easily be done together, and in the spring of 2002, the MonkeyWrench Project opened a bookstore. The money to start the store had been acquired during the previous months, when volunteers had sold books around the city and hosted fundraisers like punk rock shows. Once enough money had been secured, the group was able to acquire a brick-and-mortar storefront. Learning from the success of other stores, particularly the Wooden Shoe in Philadelphia, with which one of the founding members of MWP had been involved, MonkeyWrenchers modeled the store on a loose national network of radical bookstores within the infoshop movement. During the 1980s and 1990s, various anarcho-groups began organizing collective, radical spaces throughout the world. While these projects were not institutionally or formally allied, a commitment to alternative forms of social organization and autonomous spaces loosely knitted them together.

The rise of infoshops seems to offer an interesting and paradoxical response to the challenges faced by many radical groups. On the surface, these stores reinforce a kind of neo-liberal response to activism, insofar as the selling of merchandise is the core means for securing long-term survival. Hence, most people in Austin associate MonkeyWrench with its public commercial face as a volunteer bookstore selling left-wing books, as Eliot did when he joined the collective. Yet, the Monkeywrench collective did not open the store to serve a left-wing market or customer base. The founding collective wanted to create a public space for political education. Certainly, they saw a need to make a space for books, art, and zines that were otherwise unavailable in Austin. But there was a larger sense that a place was needed to expose people to radical ideas, whether they were anti-racist, feminist, anti-imperialist, Marxist, or anarchist, etc., and that such a place could also provide the context for a radical organizing space. In practice, MWP is more than a bookstore; it is a radical community space where a person can encounter a range of political events, mostly for free, or rally in support of some group among a wider community of activists in Austin.

How does an anti-capitalist anarchist collective commercial enterprise like Monkeywrench work? Run by radical consensus, the project resonates with alternative models of governance that privilege work/time committed as the primary means to manage collective outcomes. Monkeywrench is run by a collective, and new collective members must volunteer — and show up for — regular shifts before another collective member will nominate them for collective membership. As a collective member, volunteers can participate in deciding how the store runs. At bi-weekly collective meetings, various committees report on their activities, ask for more volunteers, and pose any decisions to the collective. Discussion ensues, usually revolving around a concrete proposal. The proposal is rejected, revised, or rephrased until everyone present is satisfied. A final proposal may be blocked by any collective member. It often happens that collective members volunteer to do more research and the collective defers the decision to the following meeting (for a more detailed outline of the process see: http://www.consensus.net/ocaccontents.html).

In practice, seniority is an important mechanism in governance, but it does not grant more formal privileges in determining the direction of the store. Rather, longer-term collective members may carry a longer institutional memory, and in sharing past dilemmas and decisions with the collective, they make significant contributions to the consensus process. But aside from these anecdotal histories, the collective does not have statutes or codes through which past decisions bear on future issues. Rather the collective depends on the oral history provided by its members. The collective codifies nothing, and it has no laws; therefore, it decides on the merit of each new proposal as it arises. This means that the store’s activities and commitments depend on the current collective membership to make judgments about the value and correspondence of the proposal in relation to the perceived mission of the project for the present make-up of the collective. Despite the formal horizontality of this consensus practice, there remains a recognized tension around the hidden, or silent, authority that certain people can accumulate because of their time in the collective.

But the store also profits from new collective members and volunteers and their ideas and input about changes. This continual infusion allows for useful adaptations to new circumstances and new perspectives and solutions for old problems. Due to the fact that new ideas coming from collective members are supposed to be given as much legitimacy as those that are time-tested, the collective process itself makes the project a very malleable or protean entity, and as a whole, these new inputs and different claims about how to steer the direction of the project change and benefit the project.

These improvements do not follow an evolutionary or progressive historical logic, however, because long-term collective memory is partial and sporadic. Thus, MWP reproduces itself in fits and starts, based entirely on the energies and ideas of current members. This means that questions and problems often recur, but the collective deliberates on and makes decisions about them differently each time. There is no fixed horizon, and this distinguishes its politics from campaign-oriented movements or political parties.

The political ideology of MWP is rooted in a politics of its process. It adheres to a form of radical consensus, which is a kind of ideological performance that is at times directly in opposition to dominant/hegemonic procedures for governance based upon majority voting, expertise, or rank. The decision-making process may sound rather dry and formal and can at times be painstakingly difficult, but it is the process surrounding these decisions that intrigued us most as a representation of actually existing radical democracy. In the next section we will explore the most contentious aspects of decision making at Monkeywrench, which concern creating a space for radical democracy.

Managing Inclusion and Exclusion

Collective members take the tension between openness and exclusion seriously and discuss the issue often. Openness and inclusivity are essential to the project, and much thought goes into how to support and extend them. People of various ages; racial, ethnic, and gender identifications; social standings; and occupationsvolunteer at the store. While we were at the store volunteers included high school students, women, Latin@s, Chican@s, African Americans, and people from a range of social occupations. Moreover, volunteers hold a wide variety of political ideals and commitments, from anarchism and primitivism to Marxism and liberalism. Nevertheless, there are attempts to define the limits of the project’s mission and what kinds of practices are permissible in the bookstore.

Some of the most heated debates we witnessed unfolded over books or art that ran counter to some collective members’ convictions and were, therefore, argued to run counter to the store’s general mission. In particular, the store’s fidelity to veganism resurfaced in various guises. For some collective members, maintaining a vegan space was essential to MonkeyWrench’s function as an alternative place; some contend it should have been a “vegan safe space.” There are good reasons for holding this position. Many collective members are vegan, and when the store was founded there was a commitment to having the use of the space adhere to those principles. The bookstore sold some food but it was always vegan, and some believed that carrying meat-related material in the bookstore could be seen as a promotion of non-vegan food-consumption practices.

In one instance, a collective member proposed selling some alternative cookbooks in the store. But they contained recipes with animal products, and some members of the collective believed it was inappropriate for the bookstore to carry the books. Others, however, believed that providing space for alternative books was more important and consistent with the store’s mission. To them, excluding local non-vegan books violated MonkeyWrench’s inclusiveness, particularly its commitment to an alternative economy. But as noted above, there are no formalized rules, such as bylaws, statutes, or mechanisms, that help codify an institutional memory about store practices or decisions. In many respects, past decisions do not have much bearing on present decisions or governance. Every time the issue arose, and it did, the collective was forced to debate the issue and it was that time that they decided not to carry the books.

The store’s veganism also affected the collective’s participation in community events outside the store. To raise money, members of the collective often sold books at events around the city. Community organizations enjoy having books at their events, and selling books at these events gives the store the opportunity to gain exposure and cash. A number of members of the collective proposed having MonkeyWrench sell books at an event called “County Fair in the City,” which was being hosted by two other activist, nonprofit, collectively run businesses in Austin. The store would also provide a small gift certificate to be sold at the event to help these groups raise funds. But part of the festival included a chicken show, where people’s “best chickens” would be presented to the public for a vote and the winner would receive the MonkeyWrench gift certificate. A conversation began on email about whether the project wanted to be represented at the event, and some members of the collective reacted vociferously. A torrent of arguments and responses flooded the collective’s listserv, and the situation escalated to the point where people were yelling at one another over email. The topic of discussion was a disagreement about the project’s relationship to veganism and Speciesism, as these were chickens raised for the human benefit of either making eggs or for slaughter.

In the end, the store was not represented formally at the event but this discussion soon became a debate about how the collective made “major decisions” and how collective members were interacting with one another. The argument that most resonated with collective members was not that the event did not conform to the mission and/or rules that governed the collective’s behavior but rather that the collective’s involvement in the event had not gone through a proper collective consensus process. In fact, in this case, there was a twofold breakdown in the consensus process. On the one hand, collective members should not have engaged in such a heated exchange because building consensus involves listening, not fighting. On the other hand, the proposal should have never been raised over email at all because consensus building requires face-to-face interactions.

In addition to veganism, there was also an ongoing discussion about MWP’s relationship to the state, specifically to what degree MWP endorsed state-sanctioned practices. Many people involved in the project did not believe in voting at the ballot box. Some suggested that ballot voting is not democratic because it is governed by the principle of majoritarianism, not consensus. Moreover, some held that ballet voting only reaffirms the legitimacy of the state because it is a state-making and nation-building and -affirming practice. As has already been mentioned, there is no official endorsement of any political party or person standing for elected office at MonkeyWrench, and political parties cannot hold events at the store. But there is more ambivalence around the issue of local ballot initiatives. Certainly, any member of the collective can support a ballot initiative as an individual, but the collective must reach consensus on supporting a referendum or ballot measure and on whether the store can host discussions and organizational meetings about a measure. For example, in 2008 there was a ballot measure forbidding the local government from offering subsidies to private developers. After a long discussion, the collective agreed to support the campaign, though hesitancy remained for some members.

The store was also strongly committed to supporting local artists, but this too has been a source of internal disagreement. Shift volunteers routinely buy books, zines, shirts, posters, and other merchandise from local artists, even if it will most likely not sell. However, there were times when a piece of art or its message was deemed inconsistent with the mission of the store. Once a poster of Che Guevara made by a local artist was blocked from being displayed while a poster of Emillo Zapata by the same artists was agreed upon. Some collective members objected to having MWP show support for Guevara because of his antagonistic relationship with Cuban anarchists; Zapata, it was claimed, had more affinity for anarchism and, therefore, was deemed more appropriate. Similarly, there was a long discussion about patches made by local artists, some of which said “live free or die;” those patches were removed because of that slogan’s perceived connection to more conservative political ideals.

The collective has also deemed violent and hateful (often sexist) speech as grounds for exclusion from the store, on the principle that intimidation prevents people from enjoying the store. In addition, the Austin radical community has been the subject of FBI surveillance (See Moynihan and Shane 2011), and as a consequence, there is general agreement that conversations about violence against the state endanger the existence of the store. Any speech or actions that are deemed threatening are grounds for possible expulsion. At times, this has been contentious, especially when a person’s motives and intentions were difficult to discern. While the full collective may be fully briefed about such incidents, there were times when a person working has, without the consent of the collective, asked a visitor to leave and not return. Moreover, the line between sex-positive literature, erotica, and pornography has been, at times, difficult to negotiate. Some members have argued that some of the books and zines sold at the store cross are offensive and have – both with and without asking the collective for consent — removed books because of what is perceived to be violent speech.

There have been times when measures of exclusion were seen as a way to promote inclusiveness, in particular to redress the problem of the dominance of white males in the collective and the failure to recruit the long-term participation of women and people of color. The volunteers in the store are overwhelming white, and despite efforts, there tend to be fewer women. Part of this has to do with the store’s location in a predominately white neighborhood; in addition, the people who gravitate toward anarcho-spaces in Austin, particularly punks and college-educated people, tend to be white. Because the process of consensus governance is relatively informal and can at times be combative, it has been described as “masculinist,” as people with alternative positions sometimes feel they have to struggle to be heard. Due to the fact that women have tended to spend shorter amounts of time as collective members, there is also the institutional problem that longer-term membership is male, and, therefore, institutional memory gives the impression of the project being more masculine than membership might actually be. There were discussions about having a feminist collective off-shoot or forming a subgroup that excludes straight men. A similar problem is found in the relative lack of success the collective has had in recruiting and sustaining members of color. There were attempts to create a more diverse environment and to have meetings only for people of color. Moreover, the store had events at the bookstore that drew many non-white minorities, but there is little long-term African American involvement.

Conclusion

While volunteering, we both thought a lot about how our geographical education might inform our understanding of the MWP, particularly in relation to its spatiality. As we have been stressing, within the store itself there is an attempt to create a utopian space for political action, but the project has created and engageswith an extensive space. Its support and efficacy came from how the MWP is connected to and enmeshed within larger communities of activists, alternative businesses, and politically inflected projects. People from these groups may financially help the project by buying a book at the store or giving a donation, but more importantly these are the groups that host events in the bookstore and, therefore, promote the project’s central mission to be an active community space. The stronger these connections are the stronger the project becomes, so the collective continually reflects on how it can build more effective and supportive relationships with other groups in Austin. Thus, the MWP is an example of radical space- and place-making: It works to build a larger alternative sphere of community relations, but it does so by practicing a self-reflexive governing political process based upon consensus.

The storefront, therefore, is about more than the events, books, or people occupying it. It is a transformative and productive example of radical community life in Austin. MWP is a unique gathering place for various radical people and ideas and it is productive of social action. Few, however, may realize this precisely becausethere is not an explicit political campaign or overarching vision attached to the store.

Lauren Martin is a feminist political geographer at Durham University, UK. She has researched ICE detention in Texas since 2007 and is currently researching the financialisation of detention in the US and asylum housing in the UK.

Eliot Tretter is Associate Professor in the Department of Geography and Undergraduate Advisor of the Urban Studies Program at the University of Calgary. He received his Doctorate from the Department of Geography and Environmental Engineering at Johns Hopkins University and before coming to UofC, he was a Lecturer for many years in the Department of Geography and the Environment at the University of Texas at Austin.He is author of Shadows of a Sunbelt City: The Environment, Racism, and the Knowledge Economy in Austin, published by University of Georgia Press in 2016. His latest book project, tentatively titled Petrocity, explores the complex and contradictory effects of Canada’s hydrocarbon extraction on Calgary’s urbanization. He currently resides in Calgary and grew up in Bethesda, Maryland.

References

Moynihan, Colin and Scott Shane. 2011. “For Anarchist, Details of Life as F.B.I. Target.” New York Times 28 May, 2011. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/29/us/29surveillance.html?pagewanted=all. Last accessed: 16 October, 2011.