Pole Position: Walking Formula One in East Austin

Two local designers have superimposed the new Formula 1 track on East Austin in this creative exploration of the “overlapping conditions of rapid development and stagnant urbanism” in a city divided by race and class.

0. Introduction

Turn 12: the low thwack of helicopters blades drop from the sky while tanagers, sparrows and other birds sing from the branches of trees and electricity poles. Formula One cars fly past every minute in constant doppler effect, mixing their low frequencies with the noise of airplane turbines. The traffic of highways is a furious river while, in brushy areas, cicadas mark their endless rhythms. In parking lots and on overgrown sidewalks further east the long grasses wave as the wind passes by—

Austin, Texas, keeps growing: new buildings, new restaurants, new bars, new festivals, new residents, and a new race track, the Formula One Circuit of the Americas track (COTA). Recently named the 11th biggest city in the USA, the larger metropolitan area is one of the fastest-growing regions in the country even during times of economic crisis. The eastern portion of the city, separated from downtown by Interstate 35, is historically home to minority communities, a configuration established even before the highway’s completion in the early 1960s. With its recent development efforts, Austin is experiencing a wave of gentrification that has begun displacing minority populations to the suburban fringe. This development, however, is spread unevenly through the city and as such contains gaps.

As inhabitants of the city of Austin, we wanted to investigate its urban environment in a creative, critical, and experimental manner. To this end, we designed and performed a walk that juxtaposed two aspects of Austin: fast-growing global city and local enclave. As a nomadic art practice, the walk literally transposed the distinctive shape of the COTA track over an area in the central east side of the city. This action was consistent within the tradition of psychogeography practitioners and theoreticians that have systematically used the practice of walking as a method for interrogation, critique, and survey. We invoked the situationists’ dérive method for investigating the ambiances of a city, the surrealists’ technique of transposing maps of different cities to create random excursions, and the figure of the flâneur as developed by Charles Baudelaire and Walter Benjamin as influences for writing about and discovering urban networks.i We were also inspired by contemporary artists such as Francis Alys (Paseos, 1995 – present)ii, Michael Golbreth (The Human Tour, 1987)iii and Jeremy Wood (GPS drawings, 2001-present)iv who have relied on walking as a creative process capable of unfolding stories and generating ambivalent and powerful metaphors.

The “Pole Position” walk, as we have called it, showcases contemporary gaps in Austin’s development, compares differing scales of civic perception, and serves as a tool to explore neighborhoods both literally and metaphorically. This essay captures the site, planning, and execution of the walk and offers speculation on future use of the developed technique.

1. Austin

Austin is the capital of the state of Texas. Eight of the fifteen fastest-growing cities and towns in the United States are located in the state, showcasing its rapid growth and strong economy.v Once provincial, known for its legislative or educational operations, in the last twenty-five years Austin has exploded as a major American destination. In some accounts, it is the fastest growing city in the country.vi In the year between July 2011 and July 2012, over 25,395 people moved to Austin, a rate of almost seventy per day.vii

The growth of Austin is the result of its connections to technology and music culture. Companies like Dell locate major offices here, attracting thousands of young people with disposable income. Festivals and events promote the city as a site of endless recreation, a self-proclaimed “live music capital of the world.” South by Southwest (SXSW) with its interactive, film, and music formats has shaped these creative communities, establishing a temporary nexus for tech and popular culture in mid-March. Visitors to these festivals and massive conferences leave the city buzzing about its mix of swimming holes, breakfast tacos, and drink specials, spreading the image of a carefree relaxation destination.

Major visions have already been proposed for physically updating the city. Waller Creek, a historically abused and overlooking waterway on the east side of downtown, is being tunnelized and redeveloped, along with its adjacent urban districts.viii Another proposal envisions sinking the divisive interstate, allowing additional development on the reclaimed land and reconnecting the halves of the city.ix Austin’s recent explosion gives it the capital—both financial and social—to pursue big ideas in shaping the city’s future.

This attitude also explains the recent opening of the Circuit of the Americas (COTA) track, a state of the art racing venue that is currently the only stop in the United States for the North American circuit of Formula One. The full track is a 3.4 mile loop with twenty turns. It is located southeast of the city near Austin Bergstrom International Airport (currently building its second terminal), forming an exclusive exurban racing destination. The inaugural race took place in November 2012, attracting a crowd of global elites. During that weekend, helicopters became the VIP method of travel, with sites located throughout the city for attendees to meet airborne shuttles. Though this was one weekend, the track is rented for myriad other events. The design of its observation tower showcases red tubes that cascade down to form the canopy for a music venue. According to the track website, the economic impact is estimated at between $400 and $500 million USD annually, with over 300,000 attendees present during the Grand Prix weekends.x Its presence not only introduces a new economic engine to the city but also a new scale of development.

Closer to downtown are the city’s historically ostracized neighborhoods of East Austin. The area, an established zone of Hispanic and African-American populations, was cut off from downtown first by East Avenue and then Interstate 35’s completion in the early 1960s. John Davidson, in describing the changing politics of the city, wrote that “while much of the rest of Austin has grown and prospered in the last twenty-five years, the East Side has been disproportionately neglected, marred by blight and crime and now in the throes of rapid gentrification.”xi Some districts (east 6th Street) have already been reclaimed while others (east 11th Street) are in transition. Further out, additional areas exist, and, except for the scattered of new or renovated homes, are untouched by larger acts of gentrification even as property values rise quickly. The neighborhoods—Chestnut, Rosewood, Govalles, MLK—are slightly hilly, fostering unexpected views of the city to the west and south, smaller enclaves of houses, and creek-beds choked with invasive species and litter.

Transposing the Formula One track onto East Austin showcases the difference in development and scale between the two zones. Some writers have noted the partition of Austin into two camps: the blissed, sunglasses-glad international playground, and the old, weird vestiges still surviving in its less developed neighborhoods.xii The Pole Position walk measures the two against each other with the conscious goal of making comparisons. It also presents an opportunity to engage a neighborhood on both literal and metaphorical levels, and to emerge with a renewed appreciation of local terrains and contexts.

2. Geo-locative Digital Media and Psychogeography.

As an upgrade to the psychogeographic tradition, we implemented geo-locative digital media technologies to plan, perform, and record our walk. First, we relied on internet maps, satellite imagery, computer image software, and geographic web-based applications that allowed us to trace the shape of the F1 track and re-trace it, with the same scale, in a specific area of the city where we wanted to perform the walk. Second, we relied in mobile devices such as smart phones and a personal navigation GPS device for following the drawn pathway and recording our actual walk in the form of a GPS log file.xiii Third, we used smartphones and a DSLR camera for capturing imagery and sounds of our journey.

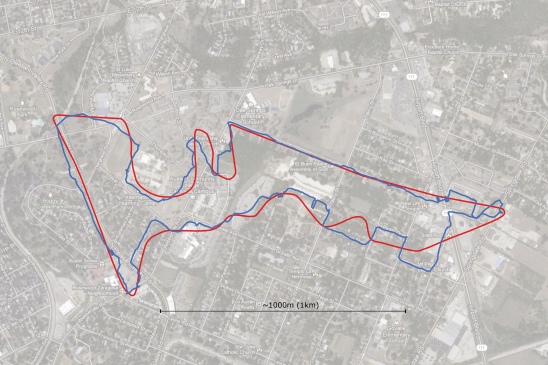

Access to digital maps and to web tools for creating GPS routes has opened not only opportunities for amateur mapping and volunteer cartography but also for experimental re-appropriation of maps, cartography and creative juxtaposition of geographic information. These technologies, particularly the web mapping resources and GPS personal navigation device, facilitated the planning, performing, and recording of our Pole Position walk.xiv For instance, accessing satellite imagery and digital maps was crucial for deciding the location of our walk and for the accurate tracing of the F1 COTA racetrack and its transposition (at a 1:1 scale) in another area of the city. To select a proper route for our dérive, the COTA track was compared with the irregular street grid of East Austin. Rotated slightly, the triangular shape of the track aligned with the axes established by Goodwin Avenue, where the regular street grid of downtown is seen, and Pleasant Valley Road, around which the creek has created irregular streets that cross the railroad tracks as they run north along the waterway. A graphic overlay was created for the purpose of navigation.

The COTA track overlaid onto the street grid of East Austin provided the orientation map for the Pole Position walk.

During the performance of the walk we constantly referenced the graphic (accessed on a smart phone) against urban surroundings, consulting a paper street map of the city, and viewing the visual display of the GPS personal navigation device. The intent was to recreate the track’s shape as faithfully as possible. Our GPS hand-held device allowed us not only keep to constant track of our position and the shape of our trajectory but also to record our movements in the hybrid space of virtual scientific geographic coordinates and the physical space of the city. The real-time feedback that we received on the screen of the GPS device was like a real-time drawing of our trajectory, as if we were creating a drawing with a continuous line. The GPS data we logged was very granular and detailed: data points with precise information of longitude, latitude coordinates, elevation, were recorded with timestamps that had the precision of atomic clocks.xv A data point was created every time we changed the direction of our trajectory. In total we recorded 316 data points during a period of 120 minutes.

3. Walking

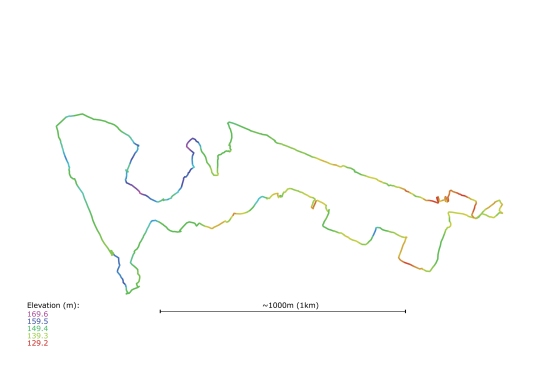

Exact GPS trace of the Pole Position walk visualized from the recorded GPS log file. Peculiaritiesof the route are explained in the body of the essay. The GPS log file provided elevational data (color coded in the visualization), adding a topographic layer of information to the chart of the walk.

The Pole Position walk was completed on a Friday afternoon in May 2013. Our performance was timed to correspond with qualifying trials for a weekend race at COTA. Whereas a single 3.4 mile loop takes an F1 driver about one minute, the analogous pedestrian lap in East Austin took us about 120 minutes. The route passed neighborhood landmarks such as the Eastview Campus of the Austin Community College, the pedestrian bridge at Airport and Goodwin, and Boggy Creek Park. Because the walk crossed both public and private properties, it required the negotiation of barriers to find the most appropriate course through an environment. A previous documentation of the walk focused on a turn-by-turn comparison of the COTA track to the walk, creating an overlay of the race experience onto the neighborhood.xvi Instead, in this essay our documentation focused on four salient issues that characterized the urban situation, action and performance: landscapes, borders, city forms, and encounters.

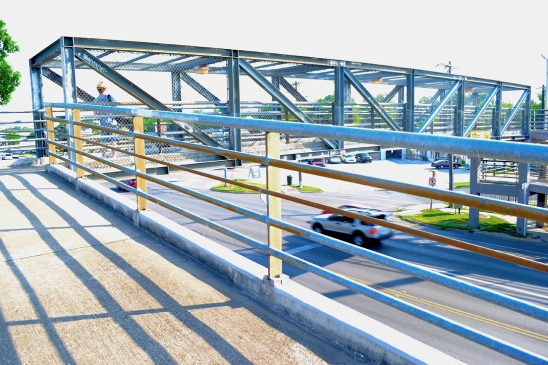

- Landscapes: The COTA track is a designed landscape, with significant changes in elevation and road angle to create a more dynamic race experience. Similar changes in elevation were experienced on the walk, from descending into debris-filled creek beds to using an overhead pedestrian crossing bridge and climbing a hill where a Boys and Girls Club campus provided views south and east. Residential areas demonstrated a range of landscaping approaches and undeveloped plots were mostly overgrown, with seasonal flowers and tall grasses in low-lying areas.

- Borders: A track is unimpeded, but a dérive through the city meets barriers—fences, trees, creekbeds, traffic, property lines. We were forced to negotiate these impediments,mostly involving traversing private property, by either scaling fences or taking detours when no clear route presented itself. Alternate routes made large changes in the resulting shape of the walk from the continuous curves of the actual COTA track. This route negotiation was constant and posed the largest threat to a faithful copy: any dead ends or detours would mar the contour of the GPS trace.

Fences were scaled where a clear route was visible but in more closed situations— directly adjacent to homes or cutting through private yards—forced an alternate route.

- City Forms: The walk was set within two main city typologies: single family homes and more recent housing and educational campuses. The walk began among the social facilities along Pleasant Valley Road before moving through an area of single family homes, a housing development and industrial area along Airport, single family homes along Goodwin Avenue, the open expanse of the ACC campus, another housing development, and the track and park areas adjacent to and under the Pleasant Valley Road overpass. Throughout the walk there were open lots and grassy fields where development has not occurred, giving the mixed use area a porosity that is typical for East Austin.

A well-worn field east of Airport Blvd adjacent to an apartment complex, industrial park, and a church.

- Encounters: A Formula One race is both solitary (for the driver) and social (for the spectators). The Pole Position walk did foster conversation between participants but was mostly solitary, with only brief conversations with others—a landscaping crew, a lone dog, a church employee, playing children—for direction or access information. Residents were seen from afar, runners jogged along a high school football field, cars passed in typical Friday rush hour congestion along Airport Boulevard.

We were not stopped or questioned at any point about conducting the walk.

Whereas a single 3.4 mile loop takes an F1 driver about one minute, the analogous pedestrian lap in East Austin took about 120 minutes. A racecar driver constantly accelerates and decelerates as dictated by the course but the speed of walking gave our experience a regular pace, with surroundings shifting at a constant rate of change. Such consistent attention to the urban environment highlighted both its oppressive normality and any deviation from ordinary conditions, however minute. Chance encounters, such as the discovery of a fence bent by the branches of a tree inside of a private yard or an abandoned sofa in the woods, hinted at pathways to continue our walk and to trace the COTA track as closely as possible.

4. Conclusions

The Pole Position walk offers lessons about Austin and its layout, in particular a new appreciation for the specific land uses of the East Side neighborhoods. The pace and trajectory of the walk gave us new views of our surroundings such as the expansiveness of code-required parking lots, the density of riparian thickets, the rural peculiarities of private houses and yards, and the stifling heat of Texas summers. Furthermore, the walk also reinforces the massive scale of the COTA track and its support facilities, a structure only possible at the periphery of a city. By locating new businesses, buildings, and interstitial terrains in our minds and allowing us to transverse different ambiences, the performative walking act expands our sense of place.

The hybrid tracing of a route, both virtually and physically, and its transposition, establishes an innovative methodology and tactic for nomadic art practices and geo-locative media performances. The added referential relationship to a “second site” (a second track) creates deeper social and spatial meanings beyond previously explored GPS-based walking techniques of improvised dérives or the conscious creation of formal shapes (GPS drawings). Tracing asymbolic urban form or feature onto another part of the city is an operation than can be repeated in many different situations, with results unique to the urban layout and the contextual setting. We intend to carry out additional similar walks and to continue developing this hybrid psychogeographic method that repositions walking as powerful medium for enacting critical questions about movement, architecture, urban networks, and technology.

i In Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography, Guy Debord wrote that “The production of psychogeographic maps, or even the introduction of alterations such as more or less arbitrarily transposing maps of two different regions, can contribute to … complete insubordination of habitual influences. A friend recently told me that he had just wandered through the Harz region of Germany while blindly following the directions of a map of London.”

ii Documentation of Alys’s Paseos and other projects can be found at http://www.francisalys.com/

iii A good review of Golbreth’s The Human Tour in Houston can be consulted at http://www.thegreatgodpanisdead.com/2009/09/enormous-forgotten-art-project.html

iv A comprehensive collection of Wood’s GPS drawings can be seen at his website: http://www.gpsdrawing.com/gallery.html

v United States of America Census Bureau. “Texas Cities Lead Nation in Population Growth,” May 23, 2013 http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb13-94.html

vi Morgan Brennan. America’s Fastest Growing Cities. Forbes Magazine. January 23, 2013. http://www.forbes.com/sites/morganbrennan/2013/01/23/americas-fastest-growing-cities/

vii USA Census Bureau.

viii Waller Creek Conservancy. Design Waller Creek: A Competition. http://www.wallercreek.org/competition

ix Reconnect Austin. http://reconnectaustin.wordpress.com/

x Circuit of the Americas. Economic Impact. 2012. http://circuitoftheamericas.com/economic-impact

xi John Davidson, “Austin At Large”, November 23, 2012. http://nplusonemag.com/austin-at-large

xii Richard Parker, “Can Austin Keep Itself Weird?”, The New York Times, October 25, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/26/opinion/can-austin-keep-itself-weird.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1&

xiii GPS logs provide a record of the journeys people make while using mobile devices with GPS capabilities The GPS personal navigation device we used, a Garmin Legend E-Trex, records logs in GPX (GPS eXchange) file format. This format is based on the Extensible Markup Language (XML) and is an open standard.

xiv Free geographic web services and applications such as http://www.gpscoordinates.eu and http://gpsplanner.net are useful for tracing routes over a map in a very easy way.

xv The GPS satellites that orbit the planet earth have atomic clocks that allow them to broadcast their signals with precise Universal Time.

xvi Additional documentation of the walk is available in the form of an interactive storytelling exercise: http://zeega.com/124022

IMAGES

All images, except Image 1, by vVvA (andres lombana-bermudez) CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Image 1 is a remix between “de la Rosa USGP” by R3d Baron (CC BY 2.0) http://www.flickr.com/photos/sphillips5615/8282228723/ and “bridge and yellow” byvVvA (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) http://www.flickr.com/photos/alombana/8781328295/.

Andres Lombana Bermudez is an interdisciplinary designer/researcher/educator and a Ph.D. candidate in Media Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

Jack Murphy is an architectural designer currently based in Austin and received his Bachelor of Science in Architectural Design from MIT.

Wow, what a cool idea, overlaying the F1 track on East Austin and then walking it. What a contrast of context and sensation, like parallel universes. Thanks!!